8/29/2006

Pre Rup

Built by Rajendravarman II in 961, this is one of the oldest temples in the region (much older than Angkor Wat). According to one of the locals named Nian, who I found perched up top of the highest of Pre Rup's turrets, the temple is seven kilometers away from Angkor Wat. (I could see the one of Angkor's spires poking out from the top of the tree line after he pointed it out.) Nian explained that the stones for Pre Rup came from Kuulain Mountain (Lychee Mountain), some 56 kilometers off. They were hauled to the site by elephant. I asked Nian why so many of temples carvings were broken. It seems that the Khmers in 961 still used stucco instead of sturdier sandstone for this work at that time. Nian asked if I understood the word stucco. "It's my language," I told him. (It's the dreadful pokey stuff that people in the 1970s used to plaster their ceilings.) The spires in the picture were partly reconstructed by an Italian arm of UNESCO five years ago.

Built by Rajendravarman II in 961, this is one of the oldest temples in the region (much older than Angkor Wat). According to one of the locals named Nian, who I found perched up top of the highest of Pre Rup's turrets, the temple is seven kilometers away from Angkor Wat. (I could see the one of Angkor's spires poking out from the top of the tree line after he pointed it out.) Nian explained that the stones for Pre Rup came from Kuulain Mountain (Lychee Mountain), some 56 kilometers off. They were hauled to the site by elephant. I asked Nian why so many of temples carvings were broken. It seems that the Khmers in 961 still used stucco instead of sturdier sandstone for this work at that time. Nian asked if I understood the word stucco. "It's my language," I told him. (It's the dreadful pokey stuff that people in the 1970s used to plaster their ceilings.) The spires in the picture were partly reconstructed by an Italian arm of UNESCO five years ago. Baphoun Cambodia

In 1908, a team of French archeologists started to clear away the vegetation covering the outer surrounding wall and three levels of a pyramid. They also built a drainage system to protect provisional sand embankments. Underneath, they discovered a 71 meter long sleeping Buddha (the monument depicted Him laying on his side). In 1918 a series of collapses occurred including the fall of half the southeast angle turret on the second level. In 1943, half of the east part of the north half of the second and third level collapsed on the first level. Nine years later, all this work was washed away in torrential rains. Civil war brought all work came to a halt in 1970. The design plans and the plans for the thousands of dismantled bricks, which had been set down in an adjacent field, were destroyed and/or lost.

Cambodian Kings

Jayarvarman II (802 – 50) Founder of Cambodian Empire

Indravarman I (877 – 89) First reservoir and Preah Ko and Bakong as well

Yasovarman I (889 -910) Moves Cambodian capital to Angkor

Jayarvarman IV (928 – 42) Usurps power, then moves capital to Koh Ker

Rajendravarman II (944 – 68) E. Mebon, Pre Rup & Phimeanakas

Jayarvarman V (968 – 1001) Ta Keo & Banteay Srei

Suryavarman (1002 – 49) Expands empire

Udayedityavarman 11 (1049 -65) Builder of Baphuan pyramid & W. Mebon

Suryavarman II (1112 – 52) Builder of Angkor Wat & Beng Mealea

Jayarvarman VII (1181 – 1219) Khmer Ozymandius: Builds Ta Prohm & Angkor Thom

Indravarman I (877 – 89) First reservoir and Preah Ko and Bakong as well

Yasovarman I (889 -910) Moves Cambodian capital to Angkor

Jayarvarman IV (928 – 42) Usurps power, then moves capital to Koh Ker

Rajendravarman II (944 – 68) E. Mebon, Pre Rup & Phimeanakas

Jayarvarman V (968 – 1001) Ta Keo & Banteay Srei

Suryavarman (1002 – 49) Expands empire

Udayedityavarman 11 (1049 -65) Builder of Baphuan pyramid & W. Mebon

Suryavarman II (1112 – 52) Builder of Angkor Wat & Beng Mealea

Jayarvarman VII (1181 – 1219) Khmer Ozymandius: Builds Ta Prohm & Angkor Thom

8/28/2006

Baksei Cham Krong

Baksei Cham Krong is located outside the gates of Angkor Thom in Siem Reap, Cambodia. In 948, King Rajendravarman chose this monument to hold the official list of Khmer kings dating back to Cambodia’s (mythical) creation. According to the text, which is carved in Sanskrit (and translated for tourists into Cambodian, English or French), the kingdom was founded by an ascetic named Kambu, who was “born from himself” and a nymph named Mera.

Baksei Cham Krong is located outside the gates of Angkor Thom in Siem Reap, Cambodia. In 948, King Rajendravarman chose this monument to hold the official list of Khmer kings dating back to Cambodia’s (mythical) creation. According to the text, which is carved in Sanskrit (and translated for tourists into Cambodian, English or French), the kingdom was founded by an ascetic named Kambu, who was “born from himself” and a nymph named Mera.

8/24/2006

Fine Litterers - Sounds Nice

Starting in September, the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) will fine those who do not keep their homes and businesses tidy within a four meter radius. The fines will be up to NT$6,000 (US$183). The EPA will also (or so it promises) pay out 30 to 50 percent of the fines it receives from litterers as reward money for those who report the crime. The biggest payouts will be NT$3,000. I wonder who's going to receive the reward money? And if the cash does actually go to people other than EPA family-members and friends, how long will this last before the program fizzles out?

8/23/2006

Foreign Laborers in Taiwan

This article on foreign workers is interesting "Government urged to prolong work visas for abused laborers". The website is http://english.www.gov.tw/TaiwanHeadlines/index.jsp?categid=10&recordid=98458

Taiwan's President Chen promised in 2000 to reduce the number of foreign workers by 20,000 per year. He also asked his cabinet to study the feasibility of imposing different minimum wages for domestic and foreign workers. It seems the president has had enough of these carpet-bagging laborers who make a starting wage of around NT$16,000 (US$480) per month and usually forfeit two months' salary to an employment broker in order to dig ditches and push the wheelchairs of discarded senior citizens around.

8/20/2006

Kinkaseki (金瓜石), Taiwan Prisoner of War Camp Survivors

Many pictures like this one exist of prisoners of war that were freed August 16th, 1945 from Taiwan's 15 prisoner of war camps. Without exaggeration, we can say the inmates looked similar to those who also emerged from Nazi concentration camps that same year. For 3.5 years, the stick-like figures of Kinkaseki, Taiwan (金瓜石) hobbled around on three teacups of watery rice stew per day. The cooks supplemented this with seaweed or perhaps a rotten vegetable or two. Japanese rice, polished and white, maggoty and mixed with all kinds of filth spelt a poor diet leading to all sorts of dieseases. These included beriberi, dysentry, pellagra, rickets, scurvy and what came to be known as "disinclinitis," meaning "no more inclination to live."

Many pictures like this one exist of prisoners of war that were freed August 16th, 1945 from Taiwan's 15 prisoner of war camps. Without exaggeration, we can say the inmates looked similar to those who also emerged from Nazi concentration camps that same year. For 3.5 years, the stick-like figures of Kinkaseki, Taiwan (金瓜石) hobbled around on three teacups of watery rice stew per day. The cooks supplemented this with seaweed or perhaps a rotten vegetable or two. Japanese rice, polished and white, maggoty and mixed with all kinds of filth spelt a poor diet leading to all sorts of dieseases. These included beriberi, dysentry, pellagra, rickets, scurvy and what came to be known as "disinclinitis," meaning "no more inclination to live." Jack Edwards - Hellhole of Kinkaseki (金瓜石)

Englishman Jack Edwards who survived 3.5 years of internment at a prisoner of war camp located in Kinkaseki, Taiwan (金瓜石) passed away on August 13, 2006.

In his book, Banzai You Bastards, Mr. Edwards described conditions at the Kinkaseki(金瓜石) camp and mine, where prisoners slaved at depths Taiwanese miners refused to go, and where they were maimed and killed in droves. According to his account, POWs were marched out at 7:00 each morning to the brow of the mountain overlooking the Taiwan Strait. They then ascended 831 steps to the entrance of the mine. From there, they went down from an altitude of 800 feet to below sea level. Picking and scraping to the light of weak carbine lamps attached to cardboard hats, POWs worked 12-hour days for stretches of 10 days at a time. Temperatures inside hovered around 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54 degrees Celsius). In some chutes, air quality was so bad (the mines were not ventilated) that POWs could only work five to six minutes before passing out.

"We would try to finish five baskets of ore each. By the time you reached the fifth basket your head would be drumming as you gasped for breath, sweat streaming from your body. You then flung down your chunkel and your basket and staggered to the ladder to be replaced by your two mates. With your heart pounding, your one thought was to get at the wat that fill the drain along the bogie rail. Here you sat, scooping up this filthy, sulfurous water and pouring it over your trunk as the steam rose from your body. You used the filthy sweat rag, now dyed yellow by constant immersion in the acid impregnated water, to wipe your face (Edwards 95-6)."

Japanese and Taiwanese guards separated the prisoners into teams of four. Each day, the guards pushed for the production of twenty-four bogeys (trolleys around three shopping carts deep) of good copper-ore. Determining the quality of the copper-ore was left to the discretion of a Taiwanese checker. Any team missing this quota would be lined up and beaten with the handle of a sledgehammer. Even worse, if imaginable, slackers were put on half-rations.

As provided for in Article 50 of the Geneva Conventions (those which Japan ratified in 1926) "POWs may be compelled to do only such work as is included in the following classes.... Industries connected with the production or the extraction of raw materials, and manufacturing industries, with the exception of metallurgical." In the extraction of copper, the inmates of Kinkaseki (金瓜石) specifically engaged in the "metallurgical." Furthermore, for the three years POWs worked the mines, medical attention was not permitted inside the premises once. Without exception, POWs were barred from departing before 6:00pm, even in cases of illness, injury of death.

It seems that multinational corporations such as Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Nippon Steel and Sumitomo in Japan, Ford, General Electric and Boeing in the United States or Volkswagen in Germany profited from WWII. At Kinkesaki, the main culprit was (besides the Japanese government and military) Nippon Kogyo Copper Mine Company, later purchased by one of Japan's largest mineral firms, the Japan Energy Corporation. Japan Energy's company profile is vague today on the details of the transaction. Although the date appears to be sometime in the mid-eighties, the company has yet to compensate anyone. Following the Second World War up until his passing on August 13, 2006, Jack Edwards fought for compensation and to expose these slave-traders.

Japanese and Taiwanese guards separated the prisoners into teams of four. Each day, the guards pushed for the production of twenty-four bogeys (trolleys around three shopping carts deep) of good copper-ore. Determining the quality of the copper-ore was left to the discretion of a Taiwanese checker. Any team missing this quota would be lined up and beaten with the handle of a sledgehammer. Even worse, if imaginable, slackers were put on half-rations.

As provided for in Article 50 of the Geneva Conventions (those which Japan ratified in 1926) "POWs may be compelled to do only such work as is included in the following classes.... Industries connected with the production or the extraction of raw materials, and manufacturing industries, with the exception of metallurgical." In the extraction of copper, the inmates of Kinkaseki (金瓜石) specifically engaged in the "metallurgical." Furthermore, for the three years POWs worked the mines, medical attention was not permitted inside the premises once. Without exception, POWs were barred from departing before 6:00pm, even in cases of illness, injury of death.

It seems that multinational corporations such as Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Nippon Steel and Sumitomo in Japan, Ford, General Electric and Boeing in the United States or Volkswagen in Germany profited from WWII. At Kinkesaki, the main culprit was (besides the Japanese government and military) Nippon Kogyo Copper Mine Company, later purchased by one of Japan's largest mineral firms, the Japan Energy Corporation. Japan Energy's company profile is vague today on the details of the transaction. Although the date appears to be sometime in the mid-eighties, the company has yet to compensate anyone. Following the Second World War up until his passing on August 13, 2006, Jack Edwards fought for compensation and to expose these slave-traders.

Patrick Cowsill

8/19/2006

Huang Chu-jen Residence (黃舉人宅)

Casteel Zeelandia at Tainan

The Dutch started to build Zeelandia in 1624 (it would take eight years to complete) after being invited by Peking to take Taiwan in exchange for leaving the Pescadores (澎湖). Zeelandia was built on a peninsula so that the fort would be able to withstand attacks originating from Taiwan itself. Surrounded by two walls, it was fortified by bulwarks and redoubts around its outer rim. From the fort on the far side of the peninsula's arm, a town called Tayouan spread southeast to northwest. Two an a half leagues in length and a quarter of a league in breadth, it was arranged as follows: Church, Weights' Official, Armaments/Blacksmith, Gallows, Slaughterhouse, Market, Prison & Alleys. The main Wharf seems to run along the tip of the far side all the way to fort walls, facing toward the inner-bay. A barren expanse of sand, Tayouan produced only pineapple trees and few other wild trees. Over 10,000 Chinese, 1,200 Dutch and number of Taiwanese aborigines called Tayouan home. A Blockhouse known as Utrecht was just above the arm of the peninsula on the near-side of Zeelandia. Described as being "a bow's shot distance from Zeelandia," it was 16 feet high and protected by stone palisades. It cut off all land access from Taiwan.

The Dutch started to build Zeelandia in 1624 (it would take eight years to complete) after being invited by Peking to take Taiwan in exchange for leaving the Pescadores (澎湖). Zeelandia was built on a peninsula so that the fort would be able to withstand attacks originating from Taiwan itself. Surrounded by two walls, it was fortified by bulwarks and redoubts around its outer rim. From the fort on the far side of the peninsula's arm, a town called Tayouan spread southeast to northwest. Two an a half leagues in length and a quarter of a league in breadth, it was arranged as follows: Church, Weights' Official, Armaments/Blacksmith, Gallows, Slaughterhouse, Market, Prison & Alleys. The main Wharf seems to run along the tip of the far side all the way to fort walls, facing toward the inner-bay. A barren expanse of sand, Tayouan produced only pineapple trees and few other wild trees. Over 10,000 Chinese, 1,200 Dutch and number of Taiwanese aborigines called Tayouan home. A Blockhouse known as Utrecht was just above the arm of the peninsula on the near-side of Zeelandia. Described as being "a bow's shot distance from Zeelandia," it was 16 feet high and protected by stone palisades. It cut off all land access from Taiwan.Dutch Influence on Taiwan Agriculture

During the 17th Century, the Dutch introduced the following items to Taiwan from abroad:

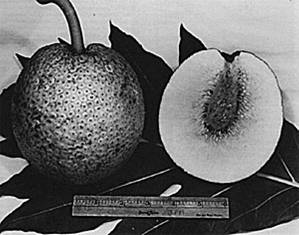

Breadfruit (above)

Jackfruit (波羅密)

Parsley

Tomatoes

Watermelon

Mangoes

Tobacco

Peppers

Lemons

Custard Apples (釋迦)

In addition to providing seeds and a market for the newly arrived Chinese settlers in Taiwan, Dutch ships also imported oxen from India to work on frontier farms.

Breadfruit (above)

Jackfruit (波羅密)

Parsley

Tomatoes

Watermelon

Mangoes

Tobacco

Peppers

Lemons

Custard Apples (釋迦)

In addition to providing seeds and a market for the newly arrived Chinese settlers in Taiwan, Dutch ships also imported oxen from India to work on frontier farms.

8/17/2006

Road to Ilan

Within the span of 35 hours, my classmates and I had made a dozen stops in our wet and winding journey through Datong (大同) and Ilan (宜蘭), beginning with Pingling (坪林) early Saturday morning and culminating in a short slog through a marshy bird sanctuary Sunday afternoon, our local escorts informing us about the comings and goings of widgeons, turtledoves and kingfishers (including the world's only known sighting and photographing of an albino kingfisher). We were an eager bunch, and yet by the end of the first day we had lost six of our comrades to various excuses. As they scurried back to their comfortable Taipei homes, the rest of us were settling in at the China Youth Corps Hotel in Ilan. We figured we would like to see this stretch of the country firsthand. Some shiny pictures in a magazine, a book or two from the National Chengchi Library or a spiffy Powerpoint presentation on Taiwan might have been enough for our less adventurous classmates, but not for us. This is the account of two remarkably beautiful places, one Taiwanese and the other Atayal (泰雅) Aboriginal, that we discovered along the way. In my opinion, both places are markers of bygone eras. Neither the Chiuliao (九寮溪) River Learning Community's Natural Ecology Zone nor the Huang Chu-jen Residence's (黃舉人宅) Haidong Academy in the Ilan Natural Center for the Arts, and in particular the ideas they encompass, has a place in the modern world.

Chiuliao (九寮溪) with its lush mountains impressed me for different reasons. In contrast to the barren and rocky peaks of the western side of the Northern American continent where I grew up, these were crowded with trees, massive ferns and other vegetation. Almost hidden within this surface of green swirls I could make out hundreds of betel nut trees, notorious for their shallow roots that give rise to landslides during typhoons. They were not planted in rows and did not seem to be in any particular order. Described in the travel literature as "an uncontaminated primitive river" with "clear and abundant water," the Chiuliao River, cutting down the center of the ecological zone, looked inviting. An informative sign at the head of the trail next to the river explained the following about the region: Wildlife abounds in the Chiuliao River area, and there are about 31 species and 68 varieties of birds, 12 species and 27 varieties of reptile, 28 species and 125 varieties of insects and 5 species and 10 varieties of fish.

On the back leg of our hike, I struck up a conversation with a local Atayal guide. After small talk, I asked her if she could speak Atayal. She explained she could not but that she wanted to learn. Hoping she would give an opinion on the betel nut trees growing up on the slopes behind us, I asked what the local community was doing to survive economically:

On the back leg of our hike, I struck up a conversation with a local Atayal guide. After small talk, I asked her if she could speak Atayal. She explained she could not but that she wanted to learn. Hoping she would give an opinion on the betel nut trees growing up on the slopes behind us, I asked what the local community was doing to survive economically:

"Right now, it is not going to well," she admitted. "Most of us have to leave if we want to work regularly."

"What can you do to earn money?" I prodded, glancing over my shoulder at the trees.

"We need to develop this area."

"How?" I asked, wondering what she could possibly mean. Did she mean building a factory? How would they build it here?

"We should plant crops like barley and fruit," she answered. The path was bringing us back to the parking lot so I nodded. This was a stock answer and I doubted I was the first person to hear it. The only things likely to get developed are another snack stand, a new brochure or a different kind of gimmick to bring in tourists. Why is it that every time we come upon aborigines in Taiwan, it is in a tourist scheme such as this?

I could not help help thinking about an essay by Hsieh Shih-chung on eco-tourism, especially after witnessing the dance performance upon arrival at Chiuliao. Writing on the Atayal of Wulai's (烏來) Shan-pao Kung-ssu (山胞公司), he states: "Aborigines in the SPKS are unwilling to admit the spuriousness of those 'traditions for sale' because it is a strategy for maintaining their living." Hsieh seems to have hit the nail on the head–imagine my surprise if our guide had turned to me and said:

"We'll probably keep on pretending to be lovely and innocent aborigines for the gawking tourists. It's the only thing we can think of doing. Besides, the government usually gives us grants if we do."

Hsieh also touches upon an experience reminiscent of Chiuliao: "In reality, the dance performance of the aboriginal women in Wulai is the most critical tourist attraction. In the performance, audiences watch ten dances. The hostess introduces them one by one in order. Tourists receive information about the colorful attire and ornamentation of the performers, and about the songs, sung in the aboriginal language. Furthermore, they are told that "all these performances are indigenous." However, in the program, these ten performances include dances of other aboriginal groups–Saisi[y]at (賽夏), Yami (雅美族), and Ami[s] (阿美). In other words, the repertoire of this Atayal dance group includes not only local dances but dances from indigenous groups all over Taiwan. Moreover, eight of the thirty people in this dance group come from ethnic groups other than the Atayal. So it seems that if one wants to get away from something like this, one must avoid arriving in a big bus with a lot non-aborigines.

The Huang Chu-jen residence (黃舉人宅), home to 19th Century scholar from Ilan named Huang Zan-syu, is an example of the U-shaped Chinese building with a courtyard. Built in 1871, it is one of the only authentic examples of architecture at the Ilan National Center of the Arts.

Huang Zan-syu as described on residence placards was a brilliant student, just one of four from Taiwan from 1821 to 1850 to pass the chu-jen (舉人) examination of the second degree (defined as an equivalent to a masters degree). The terms of the test were as follows:

1. Qualification: Applicants must already hold a chu-jen of the first degree.

2. Time:Every three years, in the eighth lunar month. The first session would commence on the ninth day of the month, the second on the twelfth and the third on the fifteenth day.

3. Fuzhou, the provincial capital of Fujian (Taiwan remained a prefecture until 1886).

4. Organization: Test Superintendent (filled by the provincial governor), Examination Officer (plus an assistant) and a General Examination Affairs Officer.

5. First Session Content: Three topics from the Four Books and one rhyming poem of five lines.

6. Second Session Content: Five topics from the Five Classics.

7. Third Session Content: Five essay questions.

Students such as Huang who passed the examination were awarded 20 taels and official robes. The government allowed them to hang a special tablet with the engraving "First in Learning" above their door.

In the rigidity of the seven before-mentioned steps, we can detect the kind of anal retentive and trivial mindset that has obviously slowed down China's development over the past 600 years (and even Taiwan in more recent times). Who cares, for instance, whether someone in a high position can write five lines of rhyming poetry? The time of the test, whittled down to certain days spaced three days apart according to lunar calendar echoes superstition more than anything. The professed goal of Confucian teaching was" to illuminate doctrines from the past and present" but the test seems lacking in the latter. The topics are not scientific or mathematical. They hardly seem to reflect the present, in this case meaning the mid-nineteenth century, a point in time well into the Industrial Revolution for many parts of the world.

Within the residence, Huang conducted his Haidong Academy. Far from enlightening students with concepts from the modern world, it seems this schoolmaster tortured them with four principle courses: reading, memorization, recitation and calligraphy. Instead of learning how to solve problems, draw designs or read and write critically, his students labored away at memorizing the necessary textbooks an official "would need to know." Those deviating from the plan were punished. Forced to kneel or stand, Huang handed them harsh reprimands. Movement to higher levels depended on both "endowment and progress of the student."

The Huang Chu-jen Residence also houses all kinds of interesting artifacts. They include an antique shaved ice machine, popsicle bags, toy tops, an abacus, coins (including taels), scales, a beautiful desk, dining sets, rice husking apparatus and so forth. Even so, I had a hard time tearing myself away from imagining the educational process, so painfully depicted at this museum. Thank god I was never a Taiwanese elementary or high school student. The display inside reads: "The school began after the 15th day of the first lunar month and ended after the winter solstice in the 12th month. Basically, school lasted all month. Classes lasted the entire month."

Several topics emerged in the places we visited in Datong and Ilan including Atayal industry and government as well as Taiwanese handicrafts, history and wildlife protection. Out of the various communities, we began to detect a common theme, an odd de-urbanization leitmotiv meant to lure people out of the cities in order to support local economies. For example, in the Pearl Community we called upon Saturday, our host spoke of the harmful influence residing in the cities has had upon the human psyche. Even though people live in cramped conditions in large population bases, he explained, they have grown isolated from each other. For him, the solution was straightforward: return to the countryside where folk still know how to smile (the mask he demonstrated turned a grimace into a smile to emphasize the point). The countryside represented a place where neighbors communicate with each other and therefore a place where this tendency to detach oneself is reversed. Visitors from the city represented, more cynically, economic support. Their stopovers would pump money into such areas. We then heard from Atayal aboriginals. Their local leaders, not surprisingly, persist in squabbling amongst themselves. They are far from implementing (or even imagining) economic solutions to allow wage-earning family members to return from Taipei, Taichung or Kaohsiung. At the National Center for the Traditional Arts, we were witness to yet another effort to strip visitors off the bigger population centers to support a more remote community and its economy. Once inside the park, our little fraternity of classmates agreed the Huang Chu-jen Residence Haidong Academy was a must-see. Mr. Huang's pedagogy fascinated us, for it captured the essence of many of Taiwan's educational institutes. Simply put, it was not hard for us to deduce that Taiwan's obsession with test-taking is certainly not a recent development. It was a pity that almost than half of the Cultural and Ethnic Structure of Taiwan class (I am not even accounting for those who missed the trip entirely) missed this center. It had good cheap food, interesting sites and lovely scenery. For those of us who braved the rain and who were able to forego our cozy Taipei shops, cafes, restaurants and living rooms for a second day, the trip was as pleasurable as it was tiring.

2-28 Memorial at Ma Ting Cheng 馬町場

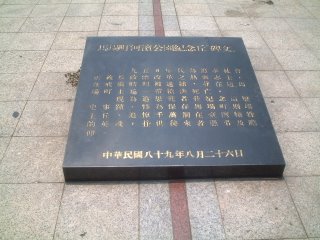

This plaque alerts passersbys of the 2-28 Massacre which took place starting in February 1947 when KMT soldiers killed 30,000 Taiwanese locals. According to the Chinese characters at the bottom, the stone wasn't set here until 2000. It blames KMT Governor Chen Yi for the bloodshed. There is however no mention of Chiang Kai-shek. Recent accounts from Chen Yi's bodyguards tell of a telegram from Chiang Kai-shek received by Chen Yi ordering him to "kill them all; keep it a secret." Lee Tung-hui, Taiwan's leader from 1988-2000, first acknowledged 2-28 in the 1990s. Ma Ting Cheng (馬町場) next to the Tamshui River (淡水) served as an execution grounds.

This plaque alerts passersbys of the 2-28 Massacre which took place starting in February 1947 when KMT soldiers killed 30,000 Taiwanese locals. According to the Chinese characters at the bottom, the stone wasn't set here until 2000. It blames KMT Governor Chen Yi for the bloodshed. There is however no mention of Chiang Kai-shek. Recent accounts from Chen Yi's bodyguards tell of a telegram from Chiang Kai-shek received by Chen Yi ordering him to "kill them all; keep it a secret." Lee Tung-hui, Taiwan's leader from 1988-2000, first acknowledged 2-28 in the 1990s. Ma Ting Cheng (馬町場) next to the Tamshui River (淡水) served as an execution grounds.2-28 / White Terror Massacre Site

Chen Yi (陳儀), Taiwan's first KMT (國民黨) Governor, was probably executed here on June 18, 1950. The site is next to the Tamshui River (淡水) in the southern Wanhua (萬華區) District of Taipei. Many of the 30,000 executions carried out by Chiang Kai-shek's troops as part of the 2-28 Massacre and his consolidation of power took place here three years earlier. Taiwanese were either shot or roped together and pushed into the river. During the era of White Terror, political prisoners were disposed of at this location as well.

Chen Yi (陳儀), Taiwan's first KMT (國民黨) Governor, was probably executed here on June 18, 1950. The site is next to the Tamshui River (淡水) in the southern Wanhua (萬華區) District of Taipei. Many of the 30,000 executions carried out by Chiang Kai-shek's troops as part of the 2-28 Massacre and his consolidation of power took place here three years earlier. Taiwanese were either shot or roped together and pushed into the river. During the era of White Terror, political prisoners were disposed of at this location as well.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Taiwan's Secret Pyramids

My friend Alain has a YouTube channel focusing on conspiracy theories, reptilians, UFOs, secret doors plus portals, sunken doors and so fort...

-

Banks in Taiwan generally refuse "foreigners" credit cards. I guess they're afraid they won't be able to recoup money (I w...

-

I came across an interesting article from June 10th, 1946 in Time , the magazine that made Chiang Kai-shek and Song May-lin "Man and Wo...

-

Here's the restroom in our commons' area. The sign reads: "Please don't use." Our cherished monkey bars We're fr...